Today was a day that has to be called inspirational. This place is real, straight up. The people are real, the problems are real and life leaves no room for superficiality. We began with a tour through the primary schools in the field opposite our hotel. It was a boarding school with about ten classes and dorms where students stayed on site. The washrooms were housed in two cement structures to the east of the property. They were dirty, of course. There is little to say about the condition of the places here in Kibaya save for their inadequacies. Speaking of such eventually loses meaning or at least intensity of meaning here. So often we see things which can be called dirty, appalling, broken, deteriorated and worse. If you’ve seen one African toilet, you’ve seen them all. It’s not to generalize or be ignorant, rather to save the repetitive and exhaustive descriptions; when it comes down to it, the toilets are toilets. The buildings are buildings; they are all broken, dirty and old.

That being said, I continue to describe. The classrooms were empty, some with chalkboards, others without. One class had desks, lined from front to back. They were the kind you see in rural education pamphlets; a bench attached to a desktop; to be shared by two or three students each.

Lou explained to us the challenges faced by these students as we sat in the library resource center where her office was. This place was beautiful; classrooms were colourful with chalkboards, a big rug and posters on the wall. Nobody learns there sadly, because the teachers lack motivation to bring their students to this special place. Teachers here are trapped in a dead end and suffocating career.

To understand the problem of rural education, consider how these ones become teachers in the first place. After form four, you must write an exam to continue your secondary schooling education. If you pass, you can carry on and finish your high school before entering university or starting your own business. If you don’t pass, you cannot carry on to finish your secondary school education. What you can do is enter into Teachers College. Being a teacher in Tanzania is not like being a teacher in the West or otherwise. Teachers do not take pride in their work and are not highly regarded in society. Ironic, when the nation is built on the foundations of Mwalimu (Teacher) Nyrere. Regardless, teaching is not an enviable post here. The wages are low- starting at about 200, 000 Tanzanian shillings per month; roughly 150 USD. Interesting, when you think my house cleaner earns 90, 000 Tanzanian shillings for two days of work per week. Further, upon graduation from teachers college, jobs are assigned randomly. Teachers do not apply for positions, rather, one day they get a letter stating where they have been posted, and then they go. Teachers from busy cities like Mwanza, Arusha or Dar es Salaam, may be sent to a village like Kibaya, where they have no family, no friends and no desire to be. Then they are given accommodation (taken out of their already pitiable salary) and they get to work. The classes may have anywhere form 50 to 120 students in them. Students pack four to a desk and sprawl on the dirt floor. There is no electricity, no water and definitely no resources. Pencils and paper are about 100 shillings each; about 7 cents. In a class of one hundred, maybe 8 will have a pencil and paper. The rest sit and listen (hopefully) so that when they have to write entrance exams they can manage a correct answer here and there.

These working conditions lead to a lack of motivation amongst the teachers, and therefore, poor quality education and high quantity corporal beatings.

Louisa told of a teacher who is a village drunk, with 50 years experience in his profession. She was shadowing a class of his when he walked through the rows to hear each student reply to one of his questions. A student in the class is autistic or otherwise challenged.

“Wewe!” the mwalimu shouted as he slammed his stick on the table in front of the boy. The teacher asked a question for which the student (obviously) had no answer. This enraged the teacher who stumbled closer and grabbed the skin on the side of the boys face. He took a clawful of his cheek and began to shake his head screaming, “ Wewe, your stupid! You know nothing!”

This teacher is regarded as one of the best in the region.

**

After the resource center we hiked up the hill about a kilometre to the only secondary school in the region. Along the way we passed the ravine where women were lined up with multicoloured buckets and bags of laundry. The pit was dry and cracked, with little water in a couple hollowed out pools. Lou pointed out the dirty water they were waiting to wash their clothes in. It looked like a mud puddle, flies hovering over the splash of dark brown water.

We carried on, shikamooing the mamas as we walked. Cows crossed our path in rows.

The air was thinner here, especially being used to sea level in Dar. The uphill walk took my breath without sending me into sweaty gulps for oxygen.

When we arrived we browsed the school; much like the last. Dirty, incomplete and crumbling all at once. The head master came and greeted us in his short-sleeved suit jacket. We sat in his office later and the students fired questions for their assessment task at him, one after the other. When they finished at least an hour’s worth of questions, we signed the guestbook and headed back to the courtyard where a few local students waited to be interviewed by our Grade 7s. One wore slick pants, a black suit shirt and long dress shoes, black leather with a white toe. Another was a Masaii boy with tribal markings burned in his cheeks. He wore purple. Fatema, one of our scarved, ultra conservative Muslim students looked back at me, “I’m scared,” she whispered with her body held awkward and gawking as usual.

Sometimes such remarks are difficult to answer effectively.

The last student was a girl about 18, in a peach synthetic pantsuit. The top was a flowing chiffon-like tunic, and the pants were bellbottomed with slits on either side. She wore beat-up black pointed heels. We matched a few of our students with theirs and off they went to tour the school with their new guides.

Us adults held back and later toured Mindy and Michael’s house at the back of the school. They were Peace Corps volunteers who would soon begin their work as the science teachers in this school.

When we finished at this school we descended the mountain for lunch at the local Tanzanian eatery; the menu featured beans and rice or chipsi mayai. We sat around the table, and I smiled at my company.

Michael was a striking looking nerd type; beautiful eyes and baggy khakis. His wife, Mindy, was short and blonde with dry red cheeks. Her eyes were quite pretty, too. Keith was an interesting fellow. He lumbered over the rest of us on lanky legs tucked in new balance runners. He wore stiff khakis, too. His face looked like the lead singer from Nickelback, with something of a goatee and a sharp nose. He spoke slowly with a sarcastic hook on each of his words. His Californian accent made his Swahili easy to understand. He got along famously with the kids, charming Francis from the start. He was Peace Corp, as well.

Louisa was British. She had a beautiful face with soft blond hair that she wore wavy down her back. She was shortish with a body appropriate for her 40 years and an African diet. She was great with the students; showed personal interest but didn’t hesitate to point out when they were being rude.

Finally, there was Flor, the German anthropologist with the mouth of an American trucker. He swore unapologetically, dropping the F-word several times over lunch with Grade 7. He was a firecracker, a lone wolf and a showstopper all in one. His accent made most of what he said funny and drinks made his wit more pronounced.

I started to wonder, Oh my gosh who am I? The overly skinny bearded guy? The moral nerds? The independent blonde with a heavy middle section?

I guess only time will tell what cassava and dala dalas will do to me. But I’m getting more moral and less skinny day by day.

**

Today was World AIDS Day. The festivities were scheduled for “Under the tree”.

After our bellies were full of starchy carbs and sticky nyama we sauntered up the hill to said tree. White plastic chairs were lined up in a half moon surrounding the emcee who spoke Swahili heavily into the mic. We made it just in time to see Masaii women perform a traditional dance. About seven of them faced the audience hopping up and down to a drum beat. Their earrings and bracelets clamoured in tune with the music. Turn by turn one or two would enter the front of the circle and shriek as she hopped relentlessly on two feet.

“Ayaaaaaaaaaaaaaa.. Iye Iye. Ayaaaaa!”

They were shy. It was beautiful.

When they finished their performance the babu returned to the mic and spoke more unintelligible Swahili. Catching sight of us he capitalized on wazungu fever. He called Lousia to the mic and Keith quickly headed for the limelight. Soon we were all ushered in front of the crowd to introduce ourselves and our mission in their village. We were to be the festival headline act, closing out the ceremony with a round of introductions.

The kids stood in their red DIA tees and Keith went through each stating names and places of origin: China, Vietnam, Dar es Salaam, America, France, Kenya and so it went until I was the last woman standing.

“Na wewe?” Babu asked in the mic, shoving it in my face not long after.

“Natoka Canada.” I giggled like a fancy teenager and looked down at the ground.

Man, those Masaii were a tough act to follow.

We started the day bright-eyed and loaded down with plaza bags full of crisps, sandwiches and assorted sweets. The grade 7s were eager to begin the field trip to a place they’d never heard of.

Incidentally, our driver hadn’t either.

We hit the road in a small bus-cum-van with curtains and seven seats. I sat in the jump seat as Mr Eric, the sarcastic Parisian French teacher took shot. Every time I travel the roads of Tanzania I am hit with a very distinct morbidity, fearing the common and the worst. For this, I did not let the students occupy my makeshift wood-back spot; it was the most dangerous seat in case of an accident. In my head I played out how I would die in several likely vehicle accidents and tried my best to keep my body relaxed. Drunk people are usually the least injured party in an accident due to their relaxed muscles; others stiffen up which makes injuries worse. I tried to think as drunk as possible and said a prayer so I’d go on good terms.

So off we went.

Five hours in and no dead bodies. We stopped for Petrol and Eric and I switched seats. This one had a seatbelt, but still, in case of an accident the front seat can just as easily be the most dangerous...

Getting out of the city in Tanzania does wonders for the psyche. Sitting still is a sort of therapy. No deadline, no control over the situation. I put on my headphones to drain out the electric Grade 7 boys and stared at the landscape speeding by. The land was flat and red. Even the Baobabs had been painted red by wind-torn clay. Savanna extended on either side of the paved path. The land was dusty and dry. At times, the shoulder was hedged in by thorny trees and pineapple fields.

I felt my brain open up as we went along. No deadlines, no studies, no service. No responsibilities lurking around the corner. To feel your brain relax is silent euphoria. Dreaming about whatever passes thorough, reflecting on what I’m doing and why.

To dream after stewing for so long really puts things in perspective. And I have never so conscientiously recognized how occupied and one-tracked my brainspace can get.

Not long after the seat swap, we turned right onto the dirt road Louisa had warned me about.

As soon as we made the turn the landscape turned velvety. The sky was softer, and heavy; almost purple. The treetops seemed thick and the earth was a creamier orange.

The further we went North, the more mountain ranges appeared and hills with large boulders piled like broken inuktuks. Clay brick huts and the odd cement and tin shack spotted the roadside at random. This was real Africa. Wazungu didn’t wander along this road often. The first half of the path was dominated by typically Tanzanian communities; kids in rags chasing goats with homemade whips in hand, mamas with green and red Jambo buckets full of water on their heads, men in Montreal Canadians hockey jerseys sleeping in the ditches and flashing thumbs up as we passed. As we wound up one particular mountain we began to enter land more occupied by Masaii tribal communities. Two young men encountered us on the road, both swathed in drapey plaid and leather belts. One of them must have been about 13. He was small and thin and carried a tiny goat under his right arm. He could have been found in the glossy pages of a coffee table book in any high culture American household. I will try to remember that picture as a souvenir of my adventures in rural Tanzania.

My wayfarers shook against my nose without stop as we cantered sloppily along the turbulent path. Stones, deep tracks and rocky soil beneath the tires made for a noisy and jolting four hours. Along the way something went loose under the van and our driver stopped to investigate. A cable had gone loose and we all clamoured out to take advantage of the opportunity to stretch.

An mzee walking towards us snoopily and silently approached. I felt a bit nervous as he had a giant but raw and primitive panga in his hands. The steel blade was bigger than a butcher knife and particularly violent in its appearance. The old man’s ears framed his face eerily; each stretched low enough to form spacers the size of birds eggs in the center. He wore ragged jeans and foam slops.

He left as he came, in silence, without a word.

We got back in the van after the girls returned from a relief expedition in the parched shrubbery out of the public eye. Rhea came back with claw marks left by thorns the length and width of toothpicks. Our trip continued til dusk when we finally peaked a hill which looked down on a small but sprawling village below.

We found the hotel with ease; moja kwa moja mpaka kijiji mwisho; straight until the end of town then left. Lou’s directions served us well. The driver sighed with relief as we pulled in the gated building with aluminum windows and a small step up to the office doors. The place was modest but of a clean appearance. The kids strayed in one hall and Eric and I found rooms in the opposite corridor. My room looked onto an African household to the back. Clothes hung on a line across the yard and chicks and roosters browsed for food on the soil below. Two houses with rolling tin roofs lined the front of the property and a thatch roof toilet sat at the back. I rolled my curtains closed as I listened to the family chat and cook. There were TVs as advertized, silver square boxes hanging above the bed a-la-hospital couture. Of course, there was no cable and only a small light in the bathroom to the right of the room. The lights from the hallway shone in my room so that I could manage to see most of what I needed. I read my Bible by laptop light and checked on the kids.

Once they were off to bed I returned and crawled in the white sheets and gave in to the stained floral and lattice blanket provided. It was cold here, especially at night. I covered my pillow with a tanktop and called it a day.

Today we went to the orphans. We hobbled through Magomeny in search of the long lost orphanage Neema had worked with for a VodaCom promotion. For weeks I had been asking her to bring. We can read them Bible stories and show the Noah video, I had offered. What an excellent way to do service and find a needy audience.

We started the trip lost on a back road in a more ghetto area of Dar. Neema parked the car and rang up Danny, a co-worker who had filmed at the orphanage, no doubt in a painfully audacious effort to advertize the benevolence of the VodaCom cellular King. We waited for Danny until he joined us and got in the car. Danny is a tall, rather handsome Tanzanian guy with a chipped off front tooth. He speaks English crystal clear; no Tanzanian or British accent. He could have been raised in an American state save for his Tanzanian shoes and that chipped front tooth.

He led us onto a few back roads and we stopped in front of a hole in a wall. Literally.

I knew we were in the right spot as children were running in and out barefoot and shaved bald. I started to feel a little awkward.

What would we do? Walk in and gather the children like chicks to a hen? I got the feeling this was something Jesus would have been better at than me. I tried to conquer the situation with that humorous over-confidence which can make any weird situation seem palatable. We entered in through the rickety doorway and greeted several mamas in kangas and colourful headscarves as they lounged on the large mattress on the floor of the entrance.

Neema and I did a round of “Shikamoos” and I felt a bit of relief as Danny greeted the ladies with more charm than I was able. We followed the skinny path through to the open space at the back of the shack. At the rear, it opened up to a crowded open-air storage and cooking space. The place was a wreck. There were old pails, bags, boxes and who knows what else piled high up along all of the walls closing in the small space. Children ran around everywhere here, coming in and out of an even more rickety shed space to the right and at the back. To the left, the house sort of sprawled into a big U. The entire space was essentially two long hallways, one of them covered in a tin roof but other than that, open. Here is where the cooking took place. A giant fry cooker sat on top of a coal fire, palm oil boiling and soot and ashes heating up the hot, moist midday air. The kids scrambled around it; a sight for sore eyes. Dad would balk at the whole situation; I could hear him in my head, “We’ll have to hire a helicopter to take you to Sault St. Marie and you’ll be ‘oh-so-surprised’”.

Sadly, there is no Sault St. Marie here.

When they burn, they salve it with honey and we hope that the mama would have the sense and cents to bring the kid to Aga Khan by morning. I doubt these kids would ever step foot inside Aga Khan; and not for lack of necessity.

Many are very sick. Neema points out Fatuma. She wears an imitation denim dress and, like the other girls, her head is shaved bald. When Neema worked with this orphanage a few years ago, Fatuma had been dropped off by an abandoning mother and left to the care of whomever should find her. She was diagnosed with AIDS not long after. They said she would die very soon. Neema was happy to see her seemingly well after a couple years of infection.

It was evident by the yellow eyes and scabbed skin of her peers that she was not the only sick one. Danny said half of them are probably ‘affected’. That’s what Africans say to avoid using the word AIDS. A little boy looked up at us as all the kids began to gather around the strangers. His face was pulled sideways below his nose; a problem that will never be solved due to his lot in life. I started to get uncomfortable with the scene. I felt we were just looking around like we were touring the Zoo or on a walking safari. I plopped down with the kids who had sat around us as we made small talk with the Babu. My butt started to burn as soon as I sat; we were gathered on the dusty cement in the back. The sun had been beating down all morning until now. It stung through my flimsy black cotton, and I stared at the kids with a hesitant smile. Neema stayed standing. I looked up at her; “Can we do something with them?”. We had big service bags and were dressed formally; I didn’t want to give the impression that we were conducting an investigation or that we were just snooping aristocrats.

It took some minutes before we decided to go into the second part of the house; the one that is half covered just beyond the make-shift kitchen. We sat on a stool there and immediately Danny wanted the camera, as Neema had told him I wanted to take pictures. I was horrified. Please don’t take pictures yet, I thought. He snapped a few as all the kids gathered at our feet and I started nervously searching for the flavoured fruit toffees I had bought at the gas station as a peace offering.

I was looking for anything to give them, some reason for our visit beyond wild curiosity or the desire to look upon the abominable circumstances of orphans in Africa.

“Put one on your lap”.

Oh God. Please. This is so embarrassing; they will think I’m just looking for a facebook post with Angelina vibes.

Finally he cooled with the photoshoot and the kids broke into song. In unison they sang a welcome song for us, “We are happy, we are happy, for our family. . .”

At one part they put their hands in the air and waved them the way deaf people clap. I threw my hands in the air and peered over at Neema. She didn’t participate. We introduced ourselves one by one. They didn’t laugh at my Swahili, and they clapped when I finished.

After they sang and I threw each child a toffee, I pulled out the Greatest Teacher Book and we announced that we would read them a story. We hadn’t chosen one in advance so as we thumbed the table of contents I pointed out the one entitled, “Do You Remember to Say Thank You?”

We turned to page 97. I started to read and Neema tried to translate. She fumbled with her words so Danny took over. He sat on a bench at the back of the kids and three little girls shared the space inside his arms.

I began- and can you believe the story starts like this:

“Did you eat a meal today?” I prayed that they had, to avoid a real awkward truth.

“Do you know who prepared it? – Perhaps your MOTHER did it. . .”

Aye. Not a good start for hungry orphans. I skipped the line about their mothers.

We continued. The story took a strange turn when it began to describe how lepers’ flesh falls off and how they were thrown out of the city and rejected by common society in Bible times. As I tried to read I held in nervous laughter and disbelief at how not ideal this story was turning out to be.

“If a leper saw another person coming, he would have to call out to warn that person to stay away from him.”

I held it in, and looked up guiltily as the children listened for the translation.

The story took ages to develop, especially translating line for line. Finally, Danny was unable to bear it anymore;

“Can we skip to the moral, this relates to saying thank-you??” he asked after I read,

“. . .when he was well, he could live with people again.”

I got the point and skipped to the last few paragraphs about the different situations we could say thank you in. I threw candies out like they were apologies and managed three little girls on my lap; including Fatuma, the little one with AIDS. The kids sucked on salty toffee as their noses ran down their faces.

My arms became sticky with as their grubby little hands pawed at me; it didn’t gross me out. I just kept peeling the papers off their candies and hoping to somehow make their day a bit better; as cliché as that sounds.

Soon we were listening as they sang their goodbye song, “We are happy, we are happy to say goodbye. . . .” This time they clapped at intervals.

I eyed up one little girl with a tiny oval face and hands the size of a baby’s. Her round head was covered in a blue headscarf, she was awful little to wear a head covering so I wondered if it was for reasons of faith or health. I gave her another candy.

We said our goodbyes and climbed back in the blue SUV outside the upside down house.

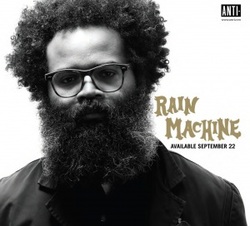

"Kurt Cobain knew the truth: “This is off our first record. Most people don’t own it.” Applause.

It was late autumn in 1993 and Nirvana had just settled down in front of MTV cameras to begin rolling one legendary live take most know simply as Unplugged. The song they were about to claw into was “About a Girl,” a pop number originally tucked away in a cauldron of sludge and growl named Bleach, Nirvana’s first and rawest-by-a-mile studio album from 1989. It wasn’t just a debut record most people didn’t own, it was a record nearly unknown to almost everyone.

Mostly because of the web, but starting with the four chords that kicked off “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the game has changed entirely since Bleach’s birth. By the time a release is scheduled to rest on a record store shelf, it’s already been out for weeks if not months. Records can’t sneak up on us anymore. Nevermind’s hefty legacy is clear: triggered an altrock revolution, cemented Seattle’s place on the cultural map, changed popular music forever and this list could get long.” – David Bevan

For more, see Fader mag, issue 64.

Janka Nabay of Sierra Leone.

In the post-Janka landscape, young people from Sierra Leone to Liberia are jammingbubu. “I started this music by saying ‘love your culture,’” says Nabay, better known asthe Bubu King. Check the anti-war song, “Sabano.” “[It] means ‘we all hear,’” he says. “I had to make a record to warn[the rebels] to stop. And they hate me right now.They forced me to moveout of the country.”“I STARTED THIS MUSIC BY SAYING ‘LOVE YOUR CULTURE.’”

An old man left the gate as I negotiated my bijaj trek from Mlimani.

He wore a Muslim cap and a long overshirt. I ‘shikamoo’ed him, of course. That was a bad idea. He inched close and chomped a fairly crunchy toothpick. “Hujambo, Unapenda samaki?”

“Napenda.”

“Samaki gani?”

Fumble with words . . . “Kila samaki.”

He listed off all the types of samaki available in Dar; Red Snapper, Tuna, Blue Fin, etc. etc.

I smiled and shook my head, ‘Oh yes, I like them all.”

“Unakaa wapi?”

I was confused. I assumed he must know where I stay as he left from my gate and I therefore assumed he was the Ethiopian neighbours friend or baba.

It’s hard to be vague in Kiswahili, especially when you are paying off a bajaj and clearly close to home. We entered into a culturally and linguistically confusing discourse, him insisting to bring me samaki, and me trying to be non-committal, stand my ground in Kiswahili, and discern whether he was being a friendly babu, a pervert or a determined salesman. All the while, Joseph the neighbour askari and the bajaj driver stood and watched in the dark. My askari stood there too, except he so conveniently released all details of my house location and agreed that should he come to see me they would let him right on in. Hm, he's my security guard?

My other askari ran around the corner to break my 10 so I could pay the driver as he had no change. This made the whole charade much longer, which may have been a good thing as it took me quite a while to get up the nerve and find the right moment to ask what the hell was actually going on.

I couldn’t tell if he was being generous and gifting me some fish, or if he was looking to catch a sale. I did not want to insist he not bring the fish if indeed it was a gift, as that may be offensive especially as he was an old mzee. But, I didn’t want the fish. And as he tried harder and harder to explain he would come jioni kesho, I realized more and more he was making some definite arrangements.

“Ninahitaji kulipa kwa samaki?”

“Yes.”

OK, no thanks then. I don’t want to pay for fish from a street Babu who knocks down doors for samaki sales.

Yesterday I received a text form Norma. We were meant to do service today after my work.

“Dear Jody. I am so so sorry. I cannot come because I have severe malaria. I am under sever dosage. Enjoy the ministry. Norma.”

Norma is a Kenyan sister in my hall, about 34 maybe. She usually wears her hair in a row of braids meeting at the very top of her head in a little square sprout which sticks up like alfalfa. She has a round face, steel rimmed glasses, and her chest swells out like 2 beach balloons filled with sand.

Norma is schizophrenic. “Sometimes,” she told me, “I think I am the faithful and discreet slave . . . but I’m not (giggle).” She cannot speak to most men, except David Livingstone who she hopes to marry if her texts can charm him sufficiently. She thinks most men have fallen in love with her, and once told me a story of her neighbour’s children being killed by their uncle with an axe. I’m not sure if that was true.

I told her I would come visit her instead of working in the ministry together, hoping to cheer her a bit and worrying about the sounds of “severe malaria”.

After work, I realized that the timing would be off if I had to take dala-dala because Deb and Kirstin cancelled on me. I wouldn’t be able to visit long because it would become dark soon after my arrival. I texted her asking if I should come Saturday for lunch instead.

“I will wait for you at 5:30 and I have planned to buy you warm apple juice at the mall. About Sat, I will ask my sis. I am sure she will accept like 2day. Norma.”

I could not cancel. So I went. I could not find her inside the entrance so I went out to the platform heading towards the University. I could not see her, I scanned the small crowd and gave her a ring.

“I’m here, where are you?”

“I’m here, too.”

I spotted a white bum sticking high in the air as its owner crouched low to the ground and buried her head in her knees in order to take a call.

“Um, I think I see you.”

I hung up and up swung the head belonging to the white skirt. She wore a long canvas skirt, red rubber sandals and a hand-knit wool top that could go up against the best of classic Christmas sweaters. Her smile became huge as I approached and hugged her. She was brighter than I have ever seen her and as we headed towards the mall to retrieve warm apple juice, she nearly laughed through her curled up lips. I knew I had not wasted my time on this visit.

She was pleased as punch to be buying juice for me, and in return, I felt honoured as she pulled her alfutano out and bought the box for me. I knew her allowance was monthly and very modest. Just enough for the dala-dala for ministry and some warm milk.

“My sister told me to buy it for you.”

We headed towards her house across the way, her walking at beat-neck speed. I commented on her quick pace and she said, “I am not well, in my mind.”

I decided to just walk faster.

When we got to her road she sheepishly told me their road was not paved.

“Neither is mine.” I replied.

We walked into the shamba kidogo and finally stopped at a white gate. I was expecting to be led to the servants quarters behind the house as she had referred to staying at the servant’s quarters of an mzee we ran into in the mall.

Her small nephew, Adrian, led us into the house instead. It was very nice, and Adrian smiled such a curious and charming smile as he escorted us in.

I sat in a love seat with giant leapord print cushions and asked him what he had learned in school that day.

“Tables and how to feed a camel.” His eyes were expectant and eager to entertain. His two front teeth were too big for his mouth and seemed to announce his presence. His mouth was always open, and a smile- always crouching in the corners of his cheeks.

“How to feed a camel? Did you see a camel today?”

“No, we just learned how to feed one.”

“Have you ever seen a camel?”

“No.”

(Norma had, on her way to Nairobi in a small village, but not in a zoo).

“Tell me how to feed a camel.”

“First, you must wash your hands,” he demonstrated. “Next, you hold your hands out like this,” he cupped his little hands together and set them out from his body. He mimed pushing it to the camel’s mouth and keeping his palms flat when he opened his hand. “Third, you wash your hands again.”

He listed off the answer, and waited to see if I would ask more.

“Will you go to see a camel? Like at the zoo?”

“Friday.”

We moved on to tables. It was multiplication and he hates math too.

He told me he likes English, Science and HGC; History, Geography and Civics.

“That’s what I teach!”

“You learn history too?”

“No, I teach history, I’m a teacher. And I teach all three of those subjects to kids in grades 6 to 10.”

“Wow.” He enunciated the expression, and his teeth told me he really meant what he said.

He came in and out as I focused my attention back on Norma. I could have talked to him all day. Some kids just spark; you can see their brains moving through the whites of their eyes. He is one, and with such an eager little mouth, just waiting to let loose that big grin.

I returned to Norma. She poured us warm juice and we talked a bit about her medicines, her mind problems, and her plans to move to Kenya. She feels her medicines are hindering her spiritual progress. They make her very ill and she vomits and lays in bed all day due to the side effects. Her prescription is very old and psychological health in Tanzania is a difficult issue to address seriously. Many dismiss such problems as demon possession, bad luck, or complete folly. She dreams of becoming a regular pioneer and feels it would be easier in Kenya. As we persist in conversation she tells me she is not the problem, her mind is not the problem. It’s the man that’s the problem. I discern she means her brother in law. She speaks with much clarity and has the ability to reason on a variety of subjects in a totally normal way. She is not out of touch by any means. But with certain things, especially when it comes to men, she lives in another world.

She told me that he is a very nice man, and good to her, he doesn’t chase her out of the house, and he buys her food and gives her a home, but its good for couples to stay with couples, not single women with a man. She continues on about the garage next door.

“It’s very noisy, and the men are very bad. There are so many men and they are so immoral. Tanzanian men are so immoral. They just molest me and molest me all the time, when I am resting. They try to concentrate on their work but they don’t do anything because they are only thinking about me. They are hassling me and molesting me in my house.”

I haven’t figured out if we are meant to correct her when she speaks of her illusions or if we must pretend it’s real. . . I try to explain that men in Kenya will be just as bad, men like that are everywhere. She insists that Kenyan men aren’t as bad as Tanzanians, that the men are here are far more predatory.

Finally we moved on, and I spoke of Dylan’s wedding and taught her that cats are apprehensive.

We both hate cats.

She told me of how the cat would curl up on her chest when she slept on the loveseat.

“Cat’s are so immoral,” The worlds slip from her mouth in a static Kenyan accent. The last syllables of each word stick and then fall and hold just a bit. Her words are thick and heavy, and come at a constant but slow pace.

I am not sure if Tanzanian men are more immoral than Kenyans, but she is definitely right about the cats.

Being so far from home has made me a bit off; with no one to hitch my wagon to I develop stronger affinities and greater self-doubt. A bad combination for such an opinionated person.

Thankfully the kids help me keep it together; I guess Blink 182 really had something there. Noah is a creature for the books. What a special person to meet in such an already bazaar life.

Noah is about as tall as me, almost chubby and at 14, he’s reached an advanced stage of autism.

Yesterday he told me he had a dream about me (“I hate to tell you this but. . . “). That’s usually a good start.

I was not the only leading lady; I shared the spotlight with Iman and Laylah from grade 7, Miss Seren our English fleur-de-literature, and the head of the Primary Department, a Rwandese mademoiselle, Miss Pacifique (I won’t tell Mr. Eric, her frencher half).

There was lipstick. And a high-speed chase (Obviously. Haven’t you ever seen Transporter?). . . Culminating in a lipstick standoff on the football pitch. Last thing he remembers I was coming at his face with a stick of Rouge–

“I would never do that, Noah.”

“You seem scared Miss Jody”- Noah’s favourite way of acknowledging an awkward moment.

Today he emailed me, “Mrs. Jody, I would love to lead you on your final quest for Freedom in this life…”

Human nature is a funny one.

Dad wants me to write a book.

There is nothing more presumptuous than self-indulgent musings in this “blogger’s generation” and I think the last thing I need is more time with my thoughts; but I'll try.

Ps. don't tell anyone i have a blog.

|